Cultural Identity and Language Barriers: My Story as an Immigrant

My parents and me on the road, riding extremely safely on our family scooter.

by Tu My To

My parents and I arrived in the United States on October 1994, all our possessions neatly packed in several boxes and suitcases. Armed with plenty of wool coats for the ‘cold’ American (i.e. Los Angeles) climate and a few English words (Yes, No, and Thank you), our family was ready to start anew in a country we knew so little about. As my mom often told me in the years afterwards, my parents made the move because of the opportunities the United States had to offer, educational opportunities that would have been nonexistent had our family decided to stay in Vietnam. Thus, it was in hopes of a better life and a brighter future that my parents packed up our lives and settled in Monterey Park, California.

The city we decided to call home is known for its large Chinese population and its plethora of delicious Asian restaurants, but to me it was where I had gone to school, where I’d shopped for groceries with my parents, where I hung out with friends, with neighborhoods I played in and streets I had driven through. It was a city where stores had Chinese or Vietnamese words written in the front in addition to English letters and where people would greet you in Chinese because, more often than not, you’d understand what they’re saying. It was within this community that I grew up, surrounded by people whose backgrounds were similar to mine and who spoke the same languages I did.

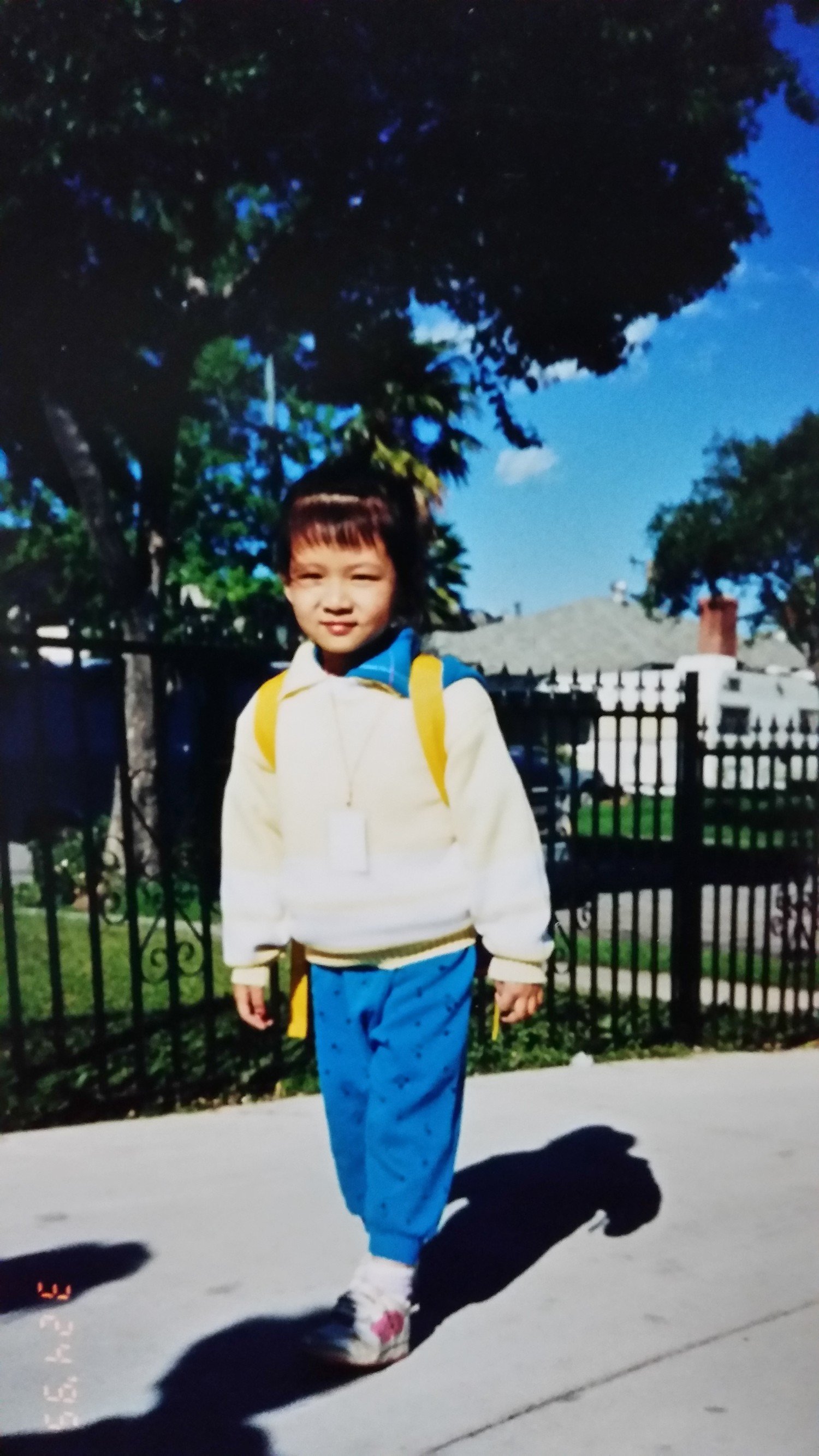

Heading home from school, fully decked in 90s attire.

Most of the classmates I had gone to school with also had parents who immigrated to the US, and many of us grew up in households where English was rarely, if ever, spoken at home. Our community molded itself to the ethnic identities of its occupants. School notices were sent home in English, Chinese, Vietnamese, and Spanish. Many of my classes had one or two teacher’s aides who spoke a second language. Our elementary school monthly calendars were marked with important dates that included Christmas, Lunar New Year, and Cinco de Mayo. It was the norm, rather than the exception, that the playground during recess and lunch breaks was punctuated by conversations in languages other than English.

Yet, many things were still difficult for my non-English speaking parents. As I spoke to the key informants for our BRAVE study, I realized that a lot of my experiences are reflected in the stories that they tell me. In particular, as the first English-speaker in the family, we often act as the spokesperson for our parents. Open house at school often meant acting as the translator for my teachers and parents. Mail at home had to be reviewed and translated. Some things I took for granted were often obstacles to my parents. How can you select the option for Chinese or Vietnamese in automated telephone menus if you cannot understand the English instructions for doing so? How do you ask questions in an unfamiliar setting if you are unable to interact with those around you?

Back then, my parents had few outlets for news or resources in Vietnamese. Today, there are plenty of over-the-air TV channels, several radio stations, a good selection of newspapers, along with numerous websites catered to many languages. However, when I was growing up, many of this did not existed. In the mid 90s, the only TV program my parents had was a fuzzy thirty-minute news segment that occurred every weekday. Over the years, the amount of resources available has grown considerably. As our key informants have pointed out, the ethnic media is one outlet immigrants often look towards to be more informed about their health, their community, and the resources available to them. While more still needs to be done, it is nevertheless exciting to see efforts being made to include everyone in the conversation.

As the years pass, I find that a lot of the memories of my initial years in the United States are fading. I remember that things were difficult, and sometimes they still are, and that adjusting to a new country was much easier for a young girl than for her parents. I also remember the teachers I've had, whose patience and guidance were always at hand. As an immigrant, there are a lot of habits and traditions that I grew up with that are still part of my life today, and I look upon these traits with pride because they are part of who I am. However, I also find that I am creating my own story, one that merges the echoes of the past, the experiences of both me and my parents’, with the present and future. It is important that we all listen to one another and share our stories because it is our histories and our experiences that shape our communities and mold us into who we are today.